Charles Reep is considered to be the first football data analyst, whose dodgy statistics encouraged managers for decades to play long ball football. With his bungle, England failed to qualify for the World Cup in 1994.

Charles Reep, former Wing-Commander in Britain’s Royal Air Force, was a faithful supporter of Herbert Chapman’s Arsenal, which revolutionized football with its W-M shape in the 1930s. During World War II, Reep was deployed in Germany, but on his return to England, he was disappointed to find that although Chapman’s system had been embraced throughout the country, the principles behind it hadn’t. On 18th March 1950 during a game between Swindon Town and Bristol Rovers he finally lost patience with Swindon’s slow and powerless playing style and inefficient scoring attempts. Reep wanted to understand Swindon’s play better, so he grabbed a pen and a notepad, and started recording the actions. According to his statistics Swindon initiated a total of 147 attacking plays, which eventually led to one goal. Reep expanded this number for the whole match, saying if a team initiates average of 280 attacking plays with an average of 2 goals scored, they need to improve only 0,71% to increase their goal average from 2 to 3.

Reep continuously took notes during matches, and quickly established himself as the first performance analyst in professional football. ‘Back in 1950,’ he wrote ‘these findings were by no means firmly established, but time was to prove them correct... Only two goals out of nine came from moves which included more than three received passes.’ He watched and recorded an average of 40 matches per season, taking him around 80 hours per match. In case of evening games, he was sitting on the stands in a miner’s helmet to illuminate his notebook. In 1951 Brentford’s manager, Jackie Gibbons offered him a part-time adviser position to help the team avoid relegation from Second Division with his statistics. With his help, Brentford doubled their goals per match ratio and secured their position in the Second Division by winning 13 of their last 14 games.

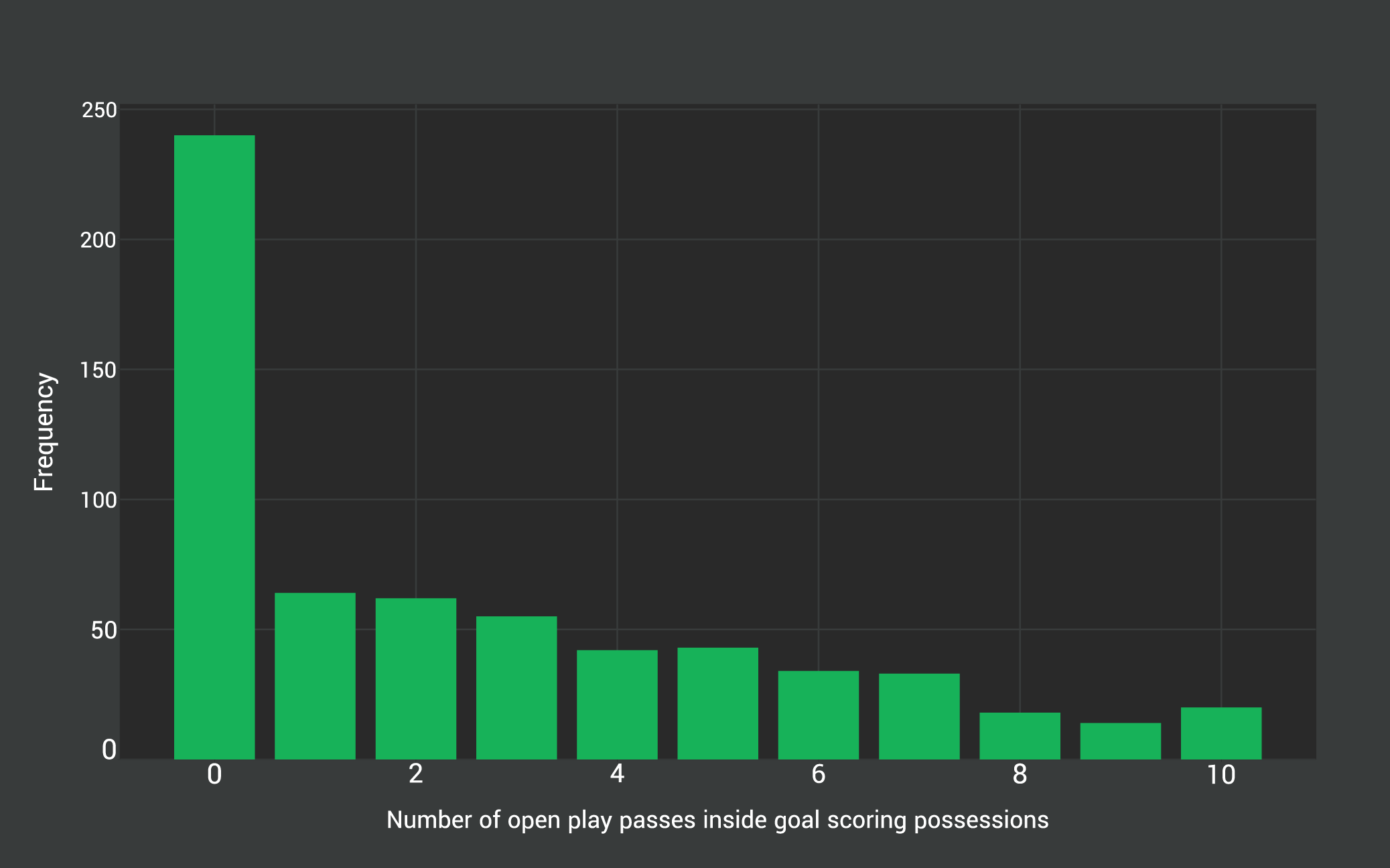

In the following season, the Royal Air Force moved Reep to Birmingham, where he met Stan Cullis, Wolverhampton Wanderers’ manager at the time. Cullis offered him a job just like Gibbons did earlier, and Reep’s calculations reinforced Cullis’ established instincts of how the games should be played, and they built a successful working relationship together. Over the years Reep developed a theory: he was convinced that too much passing was just a waste of time, in fact, it was very risky, because the teams conceded most of the goals after anarchic ball lost situations. ‘Most goals came from very short moves,’ he said, ‘the way to win is long balls forward.’

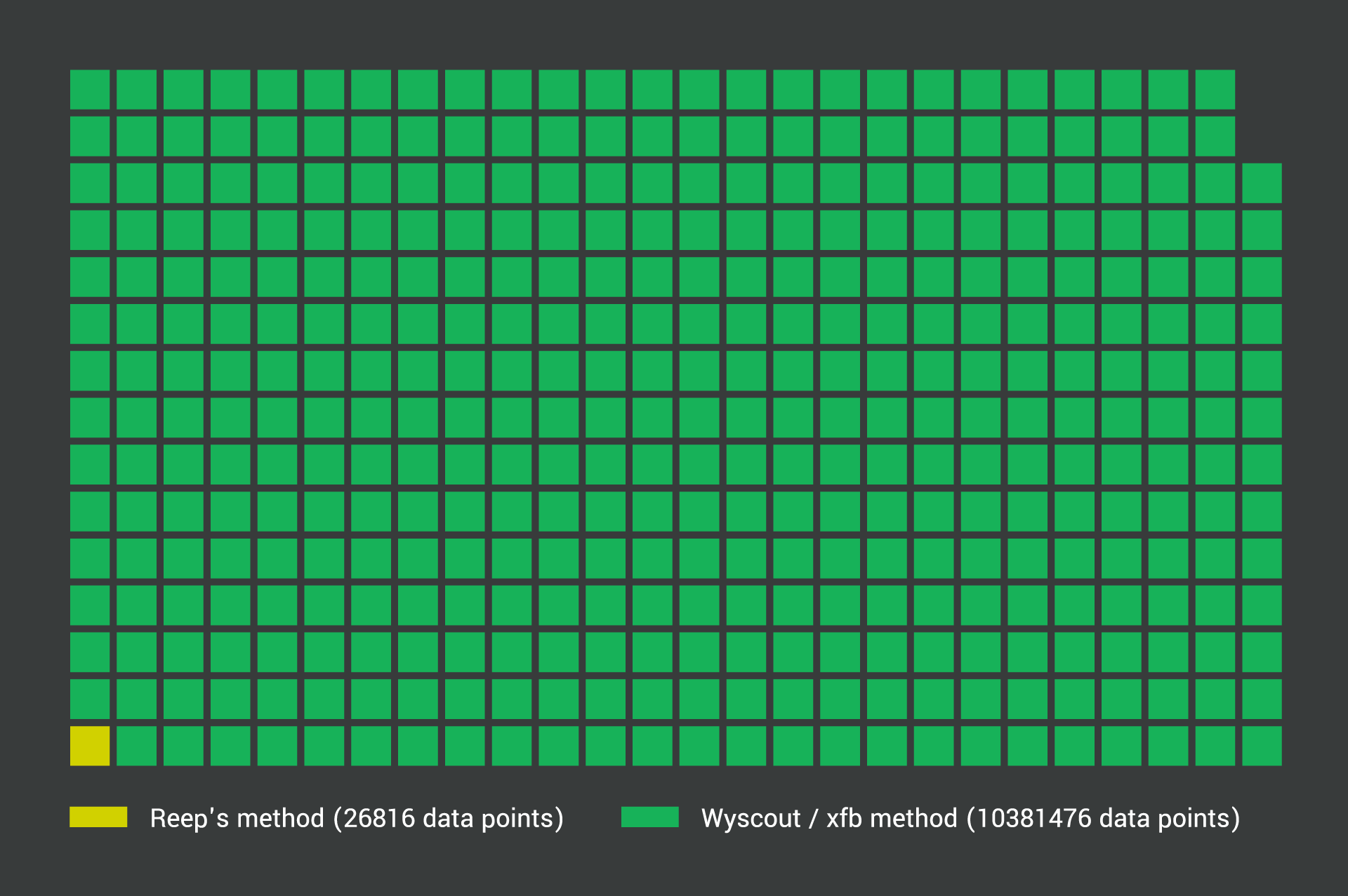

Between 1953 and 1967, he and Bernard Benjamin, head of the Royal Statistical Society, studied 578 games and discovered that only five percent of all moves consist of four or more received passes and only one per cent of six or more. Thanks to Reep’s contribution Wolves played a very primitive ’Route-one’ football, while their players practically were forbidden from lateral passes. Cullis also shared Reep’s theory of Position of Maximum Opportunity (POMO), an area a short distance from goal towards the back post from which a striking percentage of goals were scored, and into which Reep encouraged wingers to run. Under the Cullis–Reep partnership, Wolves won three First Division titles, however, as later found out, Reep’s crude concepts did more to discredit English football than to further it.

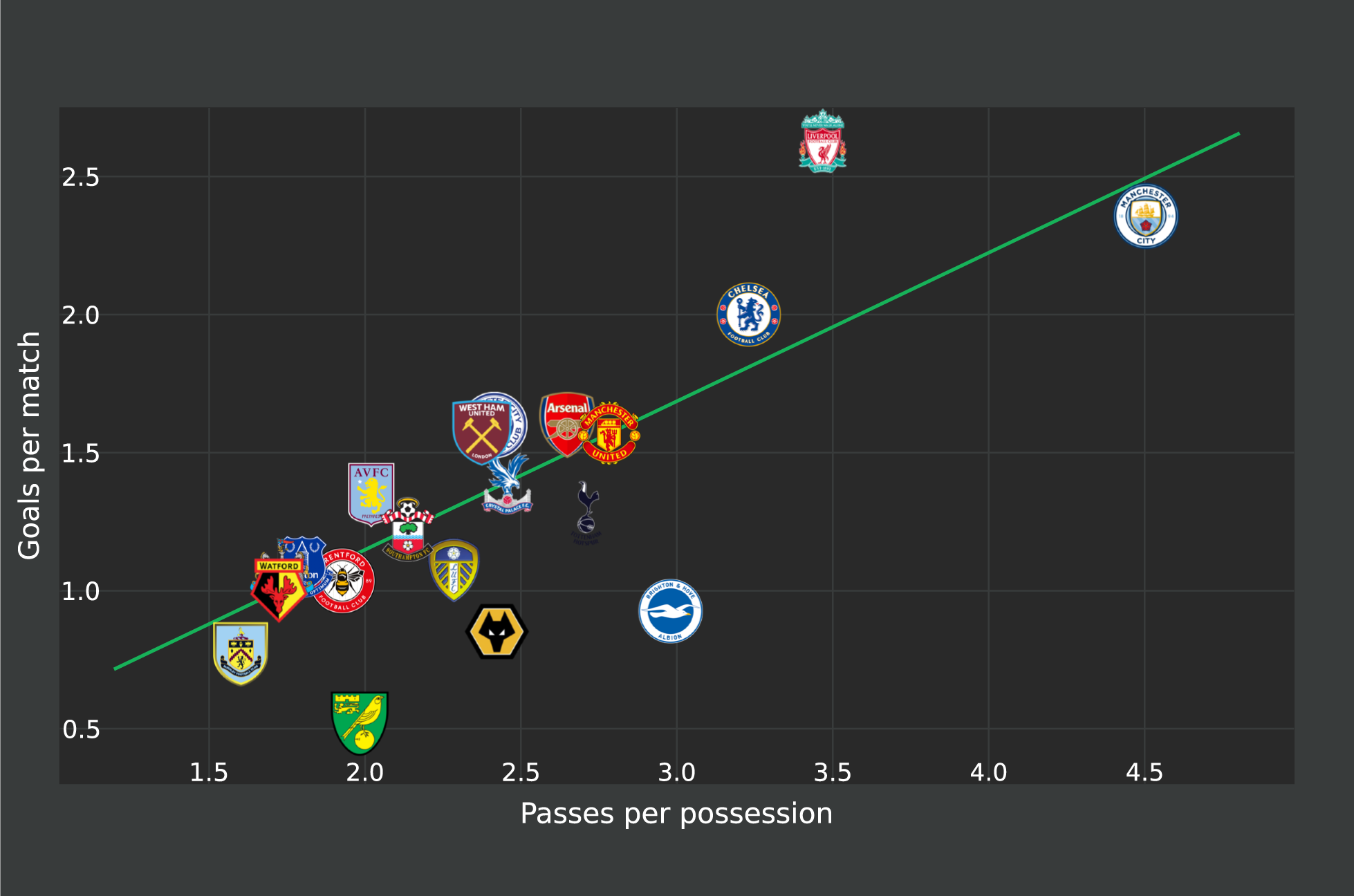

As Jonathan Wilson points out in his remarkable book titled Inverting the Pyramid, Reep’s figures show that 91.5 percent of moves in the games he studied consisted of three received passes or fewer. If the number of passes in a chain before a goal made no difference, then logically the percentage of goals resulting from moves of three or fewer received passes would also be 91.5 percent. If direct football were more effective, this figure should be higher. Reep himself claimed that ‘only two goals out of nine came from moves which included more than three received passes’ (so seven out of nine came from moves of three or fewer). If, as those figures suggest, roughly 80 percent of goals result from moves of three received passes or fewer, but 91.5 percent of moves consist of three received passes or fewer, then it surely follows that moves of three passes or fewer are less effective than those of four or more. And these figures do not even take into account the goals scored when long chains of passes have led to a dead-ball or a breakdown; or even the fact that a side holding possession and making their opponents chase is likely to tire less quickly, and so will be able to pick off exhausted opponents late on. The cornerstone of English football was founded on such a basic misinterpretation of figures.

In 1955 Reep retired from the Royal Air Force and was offered L750 for a one-year renewable contract by Sheffield Wednesday to work as an analyst alongside manager Eric Taylor. He spent three years at Sheffield. In his first season the team managed to get promoted to Division One, but in his final year Sheffield Wednesday had disappointing results, which led to Reep’s departure. Reep pointed his finger at the club’s key players for refusing to adapt to his direct playing style. During the remaining of his carrier, he wasn’t involved in club football anymore, but managers were inspired by his methods throughout the country. Despite the controversial statistics and critics, Reep cannot be made the main scapegoat for ruining the establishment of English football. Between 1970 and 1980 there was an ideological debate within the English Football Association (FA), whether the English national team should play possession-based or direct football. Reep voted for the latter, while Allen Wade, the Football Association’s director of education and coaching believed in the first one.

In 1983 Wade was replaced by Charles Hughes, who was a strong believer of long ball play, so Reep finally found his soulmate. From that moment on the fundamentals of English football consisted of Reep’s methods, which inspired Hughes to write his famous The Winning Formula handbook. ‘85% of goals come from five or less passes, so the best you can do is move the ball to the Position of Maximum Opportunity (POMO) zone as soon as possible’ he wrote in his book, which was the basis of how English football would be played and coached for several decades. Graham Taylor shared Reep and Hughes’ vision too. Between 1977 and 1987 Taylor was the manager at Watford, where he won four promotions in five years, and led the team to second place in Division One. In 1990 he was appointed head coach of the English national team, but when England failed to qualify for the World Cup in 1994, Taylor resigned. Hughes kept his title as the FA’s director of education and coaching for one more year, then he left too. With England’s disappointing results, Reep’s antiquated methods, which were considered to be the fundamentals of English football for decades, were officially over. In 1992, however, the Premier League was founded, where different European cultures have crossed their paths, and thanks to the technical evolution, the performance analyst area has started to go to a more reliable direction.

Source:

https://www.sportperformanceanalysis.com/article/history-of-performance-analysis-the-controversial-pioneer-charles-reephttps://getgoalside.substack.com/p/analytics-is-older-than-you-think

Jonathan Wilson: Inverting the Pyramid – The history of football tactics (2018.)

Simon Kuper, Stefan Szymanski: Soccernomics (2014.)

(Cover photo: Charles Reep. Source: The Sun)